In a previous post I started a series of articles about the ancient myths that gave birth to dragons, and now I want to share with you the stories of three legendary beings that are closely linked with the dragon sagas: Vritra, Typhon and Aži Dahâka.

Vritra, the Firstborn of Dragons

The Rig Veda is the first of the four Vedas, which are the primary texts of Hinduism, and it is considered one of the oldest texts in Indo-European languages. The Rig Veda contains several hymns called sūkta, which were probably composed in the Northeastern regions of the Indian subcontinent (India and Pakistan) between 1500-1200 BC, and they were eventually written in Vedic Sanskrit around 600 BC. These hymns were dedicated to the work and feats of certain Vedic divinities, some of whom were essentially deified natural phenomena. Indra, the god of lightning, thunder, storm, rain and the rivers is one of them, and his fight against the dragon Vritra is one of his greatest exploits. Vritra held the waters of the rivers captive, thus threatening the progress of humankind, so Indra decided it was time to set the waters free. He drank Soma (a ritual Vedic beverage that was extracted from an unknown plant) in the house of Tvastar, the god of creation in the Vedas, in order to gain strength before facing Vritra. Once he drank enough Soma, Tvastar gave him the celestial lightning he forged so that he could defeat the dragon.

I WILL declare the manly deeds of Indra, the first that he achieved, the Thunder-wielder.

He slew the Dragon, then disclosed the waters, and cleft the channels of the mountain torrents.

He slew the Dragon lying on the mountain: his heavenly bolt of thunder Tvaṣṭar fashioned.

Like lowing kine in rapid flow descending the waters glided downward to the ocean.

Impetuous as a bull, he chose the Soma and in three sacred beakers drank the juices.

Maghavan grasped the thunder for his weapon, and smote to death this firstborn of the dragons.

When, Indra, thou hadst slain the dragon’s firstborn, and overcome the charms of the enchanters,

Then, giving life to Sun and Dawn and Heaven, thou foundest not one foe to stand against thee.

Indra with his own great and deadly thunder smote into pieces Vṛtra, worst of Vṛtras.

As trunks of trees, what time the axe hath felled them, low on the earth so lies the prostrate Dragon.

He, like a mad weak warrior, challenged Indra, the great impetuous many-slaying Hero.

He, brooking not the clashing of the weapons, crushed—Indra’s foe—the shattered forts in falling.

Footless and handless still he challenged Indra, who smote him with his bolt between the shoulders.

Emasculate yet claiming manly vigour, thus Vṛtra lay with scattered limbs dissevered.

There as he lies like a bank-bursting river, the waters taking courage flow above him.

The Dragon lies beneath the feet of torrents which Vṛtra with his greatness had encompassed.

Then humbled was the strength of Vṛtra’s mother: Indra hath cast his deadly bolt against her.

The mother was above, the son was under and like a cow beside her calf lay Danu.

Rolled in the midst of never-ceasing currents flowing without a rest for ever onward.

The waters bear off Vṛtra’s nameless body: the foe of Indra sank to during darkness.

Guarded by Ahi stood the thralls of Dāsas, the waters stayed like kine held by the robber.

But he, when he had smitten Vṛtra, opened the cave wherein the floods had been imprisoned.

A horse’s tail wast thou when he, O Indra, smote on thy bolt; thou, God without a second,

Thou hast won back the kine, hast won the Soma; thou hast let loose to flow the Seven Rivers. Nothing availed him lightning, nothing thunder, hailstorm or mist which had spread around him:

When Indra and the Dragon strove in battle, Maghavan gained the victory for ever.

Whom sawest thou to avenge the Dragon, Indra, that fear possessed thy heart when thou hadst slain him;

That, like a hawk affrighted through the regions, thou crossedst nine-and-ninety flowing rivers?

Indra is King of all that moves and moves not, of creatures tame and horned, the Thunder-wielder.

Over all living men he rules as Sovran, containing all as spokes within the felly.-Rig Veda, Tenth Mandala, Hymn XXXII, Indra

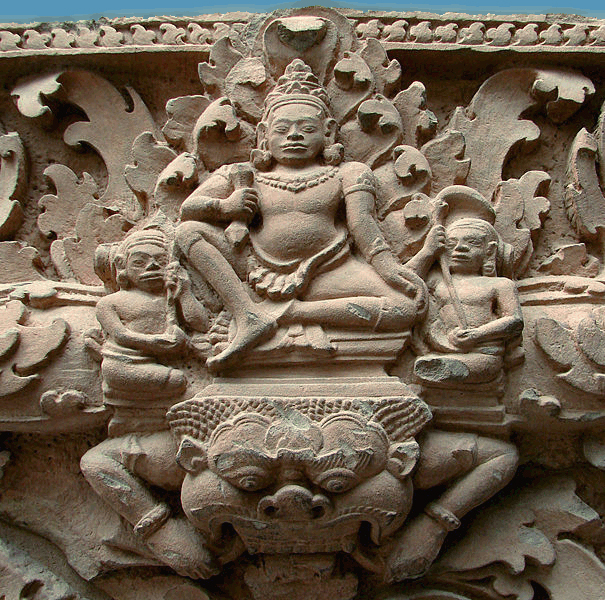

Indra subdueing Vritra, Art of Cambodia in the Musée Guimet, Paris, Reliefs of Phnom Kulen.

Because he was the one who blocked the waters and prevented them from reaching the earth, the dragon Vritra was commonly associated with draughts and deemed an obstacle for human civilization. However, according to another theory, Vritra could also personified the cold and ice from the Himalayas and the mountains from which the river Jhelum flowed before passing through India and Pakistan; in fact, it is believed that there was a huge body of water that was held by the ice of those mountains before the climate changed in that region, thus raising the temperature so as to let the Jhelum’s waters run their course (Griswold, 1999).

The battle between Vritra and Indra shares some similarities with the well-known motif of the storm-god and the deities that were associated with the most harmful natural phenomena. Perhaps the persistence and the defying attitude displayed by Vritra in the Rig Veda even before his certain defeat might have represented the slow transition between one severe season and a more favorable one.

Indra – the defeater of dragons (A. Fantalov, 2001, watercolor on paper http://fantalov.tripod.com/)

Typhon, Father of Monsters and Dragons

But when Zeus had driven the Titans from heaven, huge Earth bore her youngest child Typhoeus of the love of Tartarus, by the aid of golden Aphrodite. Strength was with his hands in all that he did and the feet of the strong god were untiring. From his shoulders grew a hundred heads of a snake, a fearful dragon, with dark, flickering tongues, and from under the brows of his eyes in his marvelous heads flashed fire, and fire burned from his heads as he glared. And there were voices in all his dreadful heads which uttered every kind of sound unspeakable; for at one time they made sounds such that the gods understood, but at another, the noise of a bull bellowing aloud in proud ungovernable fury; and at another, the sound of a lion, relentless of heart; and at another, sounds like whelps, wonderful to hear; and again, at another, he would hiss, so that the high mountains re-echoed.

Hesiod, Theogony, lines 820-835

Typhon is one of the deadliest beings in Greek mythology. He is usually described as a monstrous giant from whose body grew hundreds of heads and tails of snakes or dragons, with fiery eyes and a powerful voice that echoed in the mountains. Like many other Greek myths, there are several versions of the story of Typhon; some of the best known ones appear in the Greek poet Hesiod’s Theogony (composed around the 7th century BC), the Homeric Hymn to Apollo by the rhapsodist Cynaethus (7th century BC), the Bibliotheca of Pseudo-Apollodorus (the true identity of its author is still unknown, but it was probably written between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD), and the Dyonisiaca of Nonnus of Panopolis (4th-5th AD). Most of them tell us that Typhon was the most terrible son of Gea, a primeval goddess that personified the earth, who was conceived to destroy the Olympian gods because they had dethroned the Titans, the first children of Gea; however, after battling Zeus, Typhon is defeated and thrown to Tartarus, where he lies imprisoned. The stories also say that Typhon joined Echidna to give birth to several monsters, such as Orthrus, Cerberus, the Lernaean Hydra, the dragon Ladon, and the Colchian dragon among other mythical beasts.

Typhon, the monstrous Giant, Munich 596, Chalcidian black figure hydria, c. 540 B.C.

Photograph copyright Staatl. Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek, München

The myth of Typhon presents many of the elements of the storm god and the sea serpent legends, yet perhaps it is in the work of Apollodorus where the cross-cultural exchange between the ancient civilizations of the Middle East and Mediterranean Europe seems evident, as shown in the following fragment:

When the gods had overcome the giants, Earth, still more enraged, had intercourse with Tartarus and brought forth Typhon in Cilicia, a hybrid between man and beast. In size and strength he surpassed all the offspring of Earth. As far as the thighs he was of human shape and of such prodigious bulk that he out-topped all the mountains, and his head often brushed the stars. One of his hands reached out to the west and the other to the east, and from them projected a hundred dragons’ heads. From the thighs downward he had huge coils of vipers, which when drawn out, reached to his very head and emitted a loud hissing. His body was all winged: unkempt hair streamed on the wind from his head and cheeks; and fire flashed from his eyes. Such and so great was Typhon when, hurling kindled rocks, he made for the very heaven with hissings and shouts, spouting a great jet of fire from his mouth. But when the gods saw him rushing at heaven, they made for Egypt in flight, and being pursued they changed their forms into those of animals. However Zeus pelted Typhon at a distance with thunderbolts, and at close quarters struck him down with an adamantine sickle, and as he fled pursued him closely as far as Mount Casius, which overhangs Syria. There, seeing the monster sore wounded, he grappled with him. But Typhon twined about him and gripped him in his coils, and wresting the sickle from him severed the sinews of his hands and feet, and lifting him on his shoulders carried him through the sea to Cilicia and deposited him on arrival in the Corycian cave. Likewise he put away the sinews there also, hidden in a bearskin, and he set to guard them the she-dragon Delphyne, who was a half-bestial maiden. But Hermes and Aegipan stole the sinews and fitted them unobserved to Zeus. And having recovered his strength Zeus suddenly from heaven, riding in a chariot of winged horses, pelted Typhon with thunderbolts and pursued him to the mountain called Nysa, where the Fates beguiled the fugitive; for he tasted of the ephemeral fruits in the persuasion that he would be strengthened thereby. So being again pursued he came to Thrace, and in fighting at Mount Haemus he heaved whole mountains. But when these recoiled on him through the force of the thunderbolt, a stream of blood gushed out on the mountain, and they say that from that circumstance the mountain was called Haemus. And when he started to flee through the Sicilian sea, Zeus cast Mount Etna in Sicily upon him. That is a huge mountain, from which down to this day they say that blasts of fire issue from the thunderbolts that were thrown.

Typhon (Emily C. Martin, 2014, mixed media on board http://www.megamoth.net/)

This version by Apollodorus is somewhat similar to the myth of the serpent Illuyanka and the Hitite storm god Tarhunt: both deities are first defeated by the monsters they were facing; furthermore, they also lose those things which are vital to them –Illuyanka takes the heart and eyes of Tarhunt before he could escape, while Typhon takes the sickle from the hands of Zeus and cuts the sinews of his hands and feet. What’s more, both of them had to be assisted by others in order to recover what they had lost (Hermes and Aegipan in the case of Zeus, and Sarruma and his wife in the case of Tarhunt). On the other hand, the fact that in Apollodorus’ version the Olympian gods fled to Egypt and turned into animals might suggest an attempt to either explain or associate the Greek deities with their Egyptian counterparts (as most of us know, many of the Egyptian gods used to be represented by certain animals).

As an avatar of the destructive side of nature, Typhon is associated with the wind –both Hesiod and Apollodorus mention the powerful winds that came out from this giant–, but his imprisonment under Mount Etna (Apollodorus) and the flames that burned from his snake heads (Hesiod) may actually link him with the fire and the volcanic activity below the Earth.

Though it might not be completely accurate to consider Typhon a dragon, it is not hard to relate him to these mystical beings. Part of his body consists of dragon heads, the dragoness Delphine helped him guard Zeus’ sinews, he fathered some of the best-known Greek dragons, and his ability to spit fire from his eyes or mouth might actually be considered as one of the sources that inspired the fiery breath of dragons, an attribute that with time would be a part of the nature of the dragon.

Aži Dahāka, Destroyer of the Physical World

Thereupon gave H(a)oma answer, he the holy one, and driving death afar: Âthwya was the second who prepared me for the corporeal world. This blessedness was given him, this gain did he acquire, that to him a son was born, Thraêtaona of the heroic tribe,

Who smote the dragon Dahâka, three jawed and triple-headed, six-eyed, with thousand powers, and of mighty strength, a lie-demon of the Daêvas, evil for our settlements, and wicked, whom the evil spirit Angra Mainyu made as the most mighty Drug(k) [against the corporeal world], and for the murder of (our) settlements, and to slay the (homes) of Asha!

Zend-Avesta, Yasna IX, Hôm Yast, verses 7-8

In the Avesta, one of the most important collections of religious texts of Zoroastrianism, the ažis are the monstars that the evil spirit Angra Mainyu created to destroy the physical world (aži is the Avestan term for snake and dragon). The most prominent figure amont the ažis is the three-headed dragon Aži Dahāka, an enemy of Asha (the order of the world) and destroyer of the cities of its people, a monster that is considered one of the mightiest embodiments of evil and lie.

The yasts, the poetical hymns of the Avesta that are recited to invoke the favor of certain deities, tell us that the evil nature of Aži Dahāka was such that he even begged Vayu (a god of wind and the atmosphere) and Ardvi Sûra Anâhita (a goddess of water, fertility, healing and wisdom) to grant him their blessings so that he could vanquish all humans from the seven regions of the world (the Karshvares), yet his petition is denied despite his massive sacrifices. Aži Dahāka would eventually capture and enchant the daughters of king Yima, Savanghavâk and Erenavâk, the most beautiful women on Earth, taking them as his wives after that. Knowing this, the human hero Fereydun (Thraêtaona in Avestan) decided to rescue them, so he asked for the favor of the same divinities that denied Aži Dahāka’s desire, Vayu and Ardvi Sûra Anâhita, who do accept Fereydun’s offerings and grant him their blessings so that he could defeat the dragon.

‘Offer up a sacrifice, O Spitama Zarathustra! unto this spring of mine, Ardvi Sûra Anâhita . . . .

‘To her did Azi Dahâka, the three-mouthed, offer up a sacrifice in the land of Bawri, with a hundred male horses, a thousand oxen, and ten thousand lambs.

‘He begged of her a boon, saying: “Grant me this boon, O good, most beneficent Ardvi Sûra Anâhita! that I may make all the seven Karshvares of the earth empty of men.”

‘Ardvi Sûra Anâhita did not grant him that boon, although he was offering libations, giving gifts, sacrificing, and entreating her that she would grant him that boon.

‘Offer up a sacrifice, O Spitama Zarathustra! unto Ardvi Sûra Anâhita . . . .

‘To her did Thraêtaona, the heir of the valiant Âthwya clan, offer up a sacrifice in the four-cornered Varena, with a hundred male horses, a thousand oxen, ten thousand lambs.

‘He begged of her a boon, saying: “Grant me this, O good, most beneficent Ardvi Sûra Anâhita! that I may overcome Azi Dahâka, the three-mouthed, the three-headed, the six-eyed, who has a thousand senses, that most powerful, fiendish Drug,

that demon, baleful to the world, the strongest Drug that Angra Mainyu created against the material world, to destroy the world of the good principle; and that I may deliver his two wives, Savanghavâk and Erenavâk, who are the fairest of body amongst women, and the most wonderful creatures in the world.”

Ardvi Sûra Anâhita granted him that boon, as he was offering libations, giving gifts, sacrificing, and entreating that she would grant him that boon.

‘For her brightness and glory, I will offer her a sacrifice . . .

Zend-Avesta, Yast V, Âbân Yast, Chapters VIII-IX, verses 28-35

I will sacrifice to the Waters and to Him who divides them . . . .

To this Vayu do we sacrifice, this Vayu do we invoke . . . .

Unto him did the three-mouthed Azi Dahâka offer up a sacrifice in his accursed palace of Kvirinta, on a golden throne, under golden beams and a golden canopy, with bundles of baresma and offerings of full-boiling [milk].

He begged of him a boon, saying: ‘Grant me this, O Vayu! who dost work highly, that I may make all the seven Karshvares of the earth empty of men.’

In vain did he sacrifice, in vain did he beg, in vain did he invoke, in vain did he give gifts, in vain did he bring libations; Vayu did not grant him that boon.

For his brightness and glory, I will offer unto him a sacrifice worth being heard . . . .

I will sacrifice to the Waters and to Him who divides them . . . .

To this Vayu do we sacrifice, this Vayu do we invoke . . . .

Unto him did Thraêtaona, the heir of the valiant Âthwya clan, offer up a sacrifice in the four-cornered Varena, on a golden throne, under golden beams and a golden canopy, with bundles of baresma and offerings of full-boiling [milk].

He begged of him a boon, saying: ‘Grant me this, O Vayu! who dost work highly, that I may overcome Azi Dahâka, the three-mouthed, the three-headed, the six-eyed, who has a thousand senses, that most powerful, fiendish Drug, that demon baleful to the world, the strongest Drum that Angra Mainyu created against the material world, to destroy the world of the good principle; and that I may deliver his two wives, Savanghavâk and Erenavâk, who are the fairest of body amongst women, and the most wonderful creatures in the world.’

Vayu, who works highly, granted him that boon, as the Maker, Ahura Mazda, did pursue it.

We sacrifice to the holy Vayu . . . .

For his brightness and glory, I will offer unto him a sacrifice worth being heard . . . .

Zend-Avesta, Yast XV, Râm Yast, Chapters V-VI, verses 18-25

Aži Dahāka represents several of the threats the Iranian tribes who embraced Zoroastrianism faced when they settled throughout Turkestan (the region between the Caspian Sea and the Gobi Desert). He was regarded as an enemy to the world and the principles of Zoroastrianism, and even though he does not seem to have been associated with a particular natural disaster, his capability to destroy the corporeal world and the settlements of humans might be a reminiscence of the destructive attributes of the dragons and sea serpents of the Babylonian epics. Furthermore, the Zoroastrians used to identify the lands of Bawri and the palace of Kivirinta –the very places where he offered sacrifices to obtain the favor of Vayu and Ardvi Sûra Anâhita– with Babylon and the lands of the Chaldean, the enemies of the ancient Iranian tribes (Mills, 1887).

The three heads of Aži Dahâka and his evil nature could have inspired another legend that appears in the epic poem Shahnameh by the Persian poet Ferdowsi, which was written between the 9th and 10th centuries (the Zend-Avesta was written around the 1st and 6th centuries, yet it was probably composed long before that). In the poem, Aži Dahâka seems to appear under the name of Zahhāk, an evil human king that took the crown of his father after murdering him. Soon after that, Ahriman (Angra Mainyu in Middle Persian) appeared before him under the disguise of a wonderful cook that delighted the king with sumptuous feasts for several days; when Zahhāk offered to reward him, Ahriman told him he just wanted to kiss the king on each shoulder once. Zahhāk agreed, but Ahriman vanished right after he had kissed him, and two black snake heads grew out from the same spots where his lips had touched his shoulders, which would only grew out again when he tried to cut them off. Later, Ahriman reappeared again before Zahhāk in the form of a talented physician, and he told the king that the only way he could prevent the snakes from devouring his body was to feed them with human brains, and from that point on, Zahhāk started to kill two men each day so that he could appease the snakes’ hunger. Over time, Zahhāk’s evil heart compelled him to dethrone Jamshid, the king of the world. When his vast hosts marched against Jamshid, he fled together with his army, only to be captured and killed. Zahhāk proclaimed himself as the new king of the world, and he forced the leaders of the realm to testify his legitimacy to the crown. Nevertheless, several leaders chose to support the young hero Fereydun so that he could take the throne from Zahhāk’s hands –he had previously tried to capture Fereydun due to a dream in which he was defeated by the young man. With the aid of his allies, Fereydun was able to fight and defeat Zahhāk after hitting his opponent in the shoulders, the heart and the skull. However, he could not kill Zahhāk, so he chained him below the mount Damavand, the highest volcano of Iran and Asia, where we was to remain until the end of time.

Zahhak’s dream by Juliano Zasso, from the book Armenian History in Italian Art

One very interesting feature of Aži Dahâka’s myth is the introduction of “the maiden and the dragon” theme, which also appears in the Iranian legends of certain dragon-slayers, such as Rostam and Āḏar Barzīn. The rain and the water that in the religions that preceded Zoroastrianism are guarded by a dragon or a sea serpent seem to have been replaced by the woman, who becomes the new symbol of life and fertility, which in Aži Dahâka’s myth is represented by the daughters of king Yima that are rescued by Fereydun (Russel, 1987). Also, it is important to highlight that in this story, the typical role of the storm-god has been trespassed to a human hero, a trend that will start to be common in the future dragon-slayer tales of the Middle Ages.

Aži Dahâka also plays an eschatological role in Zoroastrianism, as told by the Bahman Tast, a religious text in Pahlavi language.

“Now it is nine thousand years, and Frêdûn is not living; why do you not rise up, although these thy fetters are not removed, when this world is full of people, and they have brought them from the enclosure which Yim formed?”

‘After that apostate shouts like this, and because of it, Az-i Dahâk stands up before him, but, through fear of the likeness of Frêdûn in the body of Frêdûn, he does not first remove those fetters and stake from his trunk until Aharman removes them. And the vigour of Az-i Dahâk increases, the fetters being removed from his trunk, and his impetuosity remains; he swallows down the apostate on the spot, and rushing into the world to perpetrate sin, he commits innumerable grievous sins; he swallows down one-third of mankind, cattle, sheep, and other creatures of Aûharmazd; he smites the water, fire, and vegetation, and commits grievous sin.

Bahman Yast, Chapter III, verses 54-56

In the Zoroastrian conception of the end of times, Aži Dahâka would rise to devour great part of humanity and cause an unimaginable damage to the world; to stop him, Ahura Mazda (Angra Mainyu’s benevolent counterpart) will bring the hero Keresâsp to life, since he is the only one who can defeat the dragon without being destroyed by the wickedness that Aži Dahâka’s dead body would produce (the reason why Fereydun did not kill the dragon when he had the chance) because Keresâsp’s body is protected by the fravashi (spirit) of 99,999 righteous people. It is possible that Aži Dahâka is somewhat related to the figure of the great dragon of the Book of Revelations of the Bible or the serpent Jörmungandr of the Scandinavian Ragnarok, where the final fate of the Earth is determined by the victory of the savior and the hero over the evil that these beasts represent. This is what, in my humble opinion, makes the myth of Aži Dahâka a half-way point between the ancient dragon myths and the upcoming medieval sagas of the heroes who will face these fantastic creatures.

Corrupted dragon: Azi Dahaka (kuronneko, http://kuronneko.deviantart.com/art/Corupted-dragon-Azi-Dahaka-407202121)

References:

-Apollodorus. Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Includes Frazer’s notes. Retrieved from: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Apollod.+1.6.3

-Darmesteter, James (1882), The Zend Avesta, Part II, Sacred Books of the East, Vol. 23. Recuperado de http://www.sacred-texts.com/zor/sbe23/index.htm

-Griffith, Ralph T.H. (1896), The Rig Veda. Recuperado de http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/rigveda/index.htm

-Griswold, H.D. (1999), The Religion of the Rigveda, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited, Delhi (pp. 180-182).

-Hesiod, The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Theogony. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Retrieved from http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0130%3Acard%3D820

-Mills, L. H. (1887) The Zend Avesta, Part III, Sacred Books of the East, Vol. 31. Recuperado de http://www.sacred-texts.com/zor/sbe31/index.htm

-Russell, J.R., Skkaervo P.O., Khaleghi-Motlagh, Dj. (1987), AŽDAHĀ, Encyclopædia Iránica, Vol. III, Fasc. 2, pp.191-205. Recuperado de http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/azdaha-dragon-various-kinds

-West, E. W. (1880), Pahlavi Texts, Part I, Sacred Books of the East, Vol. 5. Recuperado de http://www.sacred-texts.com/zor/sbe05/index.htm

One thought on “Ancient Dragon Myths: Vritra, Typhon and Azi Dahaka”